박제술을 합성 미디어로 들여다 보기

A Look into Taxidermy as a Synthetic Media

이상적 동물의 이미지 혹은 쓰레기 데이터

동물을 시각 이미지로 담거나 관찰, 기록하는 행위는 인간과 비인간의 관계를 잘 드러낸다. 그 관계는 시간에 따라 인간이 동물의 존재와 이미지를 어떻게 사용 또는 오용했는가를 보여주며 동물에 어떤 문화적 의도를 새겨 넣었는지를 보여준다. 특히 예측 불가능한 야생 동물의 움직임을 포착하여 사진으로 담아내는 일은 어렵다. 인터넷에서 검색되는, 혹은 일반적인 자연 다큐 사진이 보여주는 높은 정보량을 담은 동물의 사진은 사실상 야생동물들을 바라보는 인간의 시각적 문법이 깊이 각인되어 있는 이미지라고 할 수 있다.

인간의 시각이 제거된 트레일 카메라(무인 카메라)의 경우, 카메라에 찍힌 야생동물들의 이미지는 그보다 더 다양한 위상을 드러낸다. 이러한 카메라는 인간 사진작가처럼 이상적인 포즈를 취한 동물을 포착하지 않기 (못하기) 때문이다. 동물의 예상치 못한 각도나 부분적인 모습을 무작 위로 포착한다. 따라서 인간의 시각적 틀에서는 ‘쓰기 힘든’ 사진들이 많다.

언메이크랩의 작업 과정에서도 이러한 사진들을 데이터셋 삼아 기계학습을 시키는 실험을 했을 때 흥미로운 것을 발견할 수 있는 장면이 있었다. 트레일 카메라에서 추출한 이미지―잘리거나 지나치게 클로즈업 된, 무작위의 위상을 가진 야생동물들의 이미지를 포함한―를 데이터셋으로 기계학습을 거쳐 생성했을 때, 동물들의 모습은 거의 측면이나 정면의 위상을 가진 동물의 모습으로 생성되었다. 이는 기존의 인공지능이 학습하고 있는 동물 데이터가 측면 혹은 정면 등, 인간의 시각에서 이상적인 데이터를 중심으로 학습되어 있어, 그 패턴이 전이 학습되어 생성되었기 때문으로 보인다.

혹은 트레일 카메라 푸티지는 무작위적인 포즈와 예상치 못한 각도로 인해 ‘쓰레기 데이터’로 간주될 수 있는 데이터를 만들어 내는 경우가 많기 때문에, 전처리 과정에서 제거되었을 수도 있다. 또는 멸종 위기 종일 경우, 그 물리적 희귀함으로 인해 데이터의 양 자체도 한정적이기 때문에 과소 학습되어 있기 때문일 수 있다. 이처럼 인종 및 젠더와 관련해 인간 문화에 존재하는 데이터 편향은 다른 방식으로 비인간 동물에 대해서도 일어난다. 특히 그것이 실제 환경에 적용될 때, 인간이 예측하기 어려운 더 넓은 자연의 맥락으로 인해 어긋나는 경우가 더 많이 생긴다.

이러한 작업의 과정과 리서치는 ‘동물의 초상’이라는 것이 무엇인가라는 질문을 하게 하였고, 이 글은 그 리서치 중 ‘박제술’을 중심으로 기록한 것이다. 물론 이것은 기존의 문화적 맥락만이 아니라 컴퓨터 과학이 다시 반복하고 있는 분류의 문제와 학습 데이터셋의 문제와 같이 다루어진다.

반달곰의 반달 혹은 잘못된 박제

동물의 초상을 대표하는 현재의 박제술은 동물 보존의 역사에 자리하지만 위의 예에서 보듯이 누가 왜 동물을 보존하고 싶은지에 따라 박제술은 다른 문화적 의미를 가진다. 박제술의 관행은 자연과학적 연구의 열망, 그리고 식민적 관행1으로 연결되었고, 현재는 야생동물 보존과 복원의 문제와도 연결되지만, 한편으로는 여전히 전리품 문화와도 이어지고 있다. 대부분의 박제 동물들은 죽은 후, 종의 특징을 특정 상태로 포착한 신체와 표정을 통해 살아있는 동물처럼 재현된다. 박제는 동물의 신체를 보존하는 것이지만 정확하게는 박제의 물질성은 피부를 보존하는 것이다.

이 피부에는 지금의 인간과 비인간 사이를 성찰할 수 있는 사회적 문화적 의미, 그리고 인간의 자연과 동물에 대한 통치성이 기입되어 있다. 즉 인간과 비인간 사이에 ‘박제’라는 인터페이스가 존재하는 것이다.

우리 역시 작업 과정에서 다양한 박제 동물들을 데이터셋으로 수집을 했는데, 그 박제 동물들 중에는 상당히 왜곡된 박제들이 꽤 남아 있었다. 이상한 외형을 가지고 자연사 박물관에 자리한, 혹은 수장고로 밀려난 박제들을 보며 이 박제들에 담긴 인간의 시선과 의도 역시 궁금해졌다.

1

케임브리지 대학교 라틴 아메리카 연구 교수이자 CRASSH(예술, 사회과학 및 인문학 연구 센터)의 디렉터 조안나 페이지(Joanna Page)는 제국주의, 자본주의, 백인 문화를 보존하려는 박물관의 시도의 핵심에 박제가 있었다고 말한다. “Their more critical or creative approaches have been described as “botched taxidermy,” “rogue taxidermy” or “speculative taxidermy.””, Joanna Page, Decolonial Ecologies, The Reinvention of Natural History in Latin American Art, Open Book Publishers, May 3, 2023, p. 201 ( https://books.openbookpublishers.com/10.11647/obp.0339/ch6.xhtml)

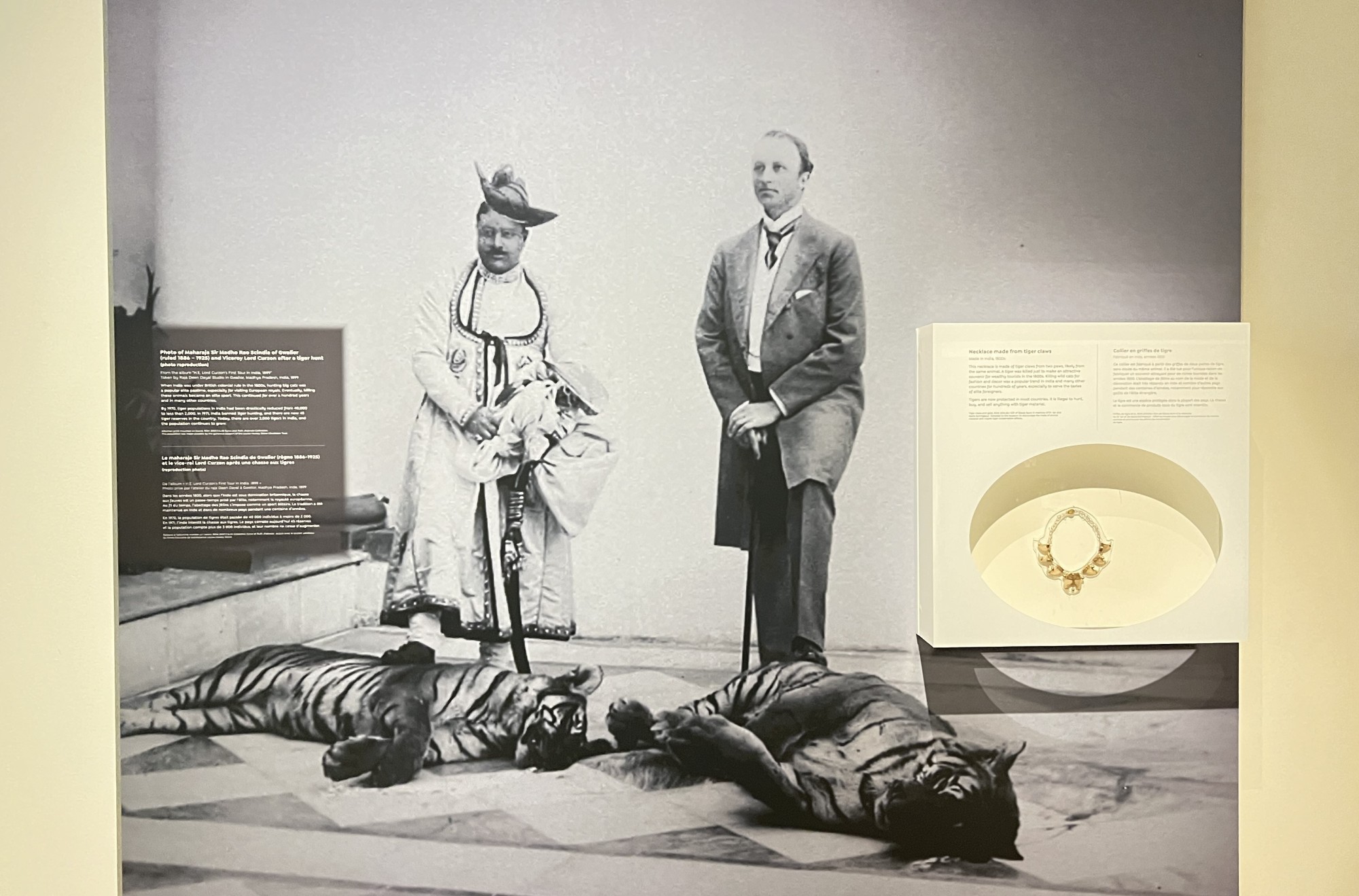

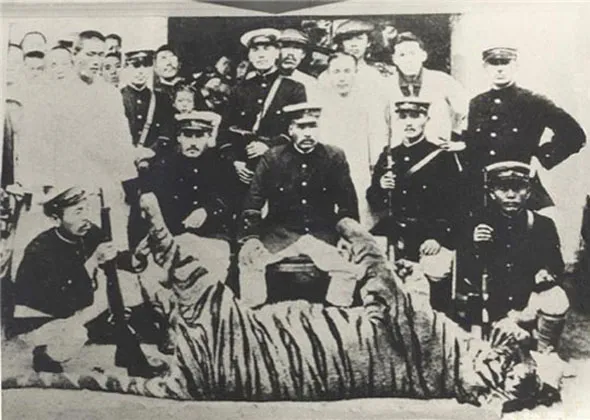

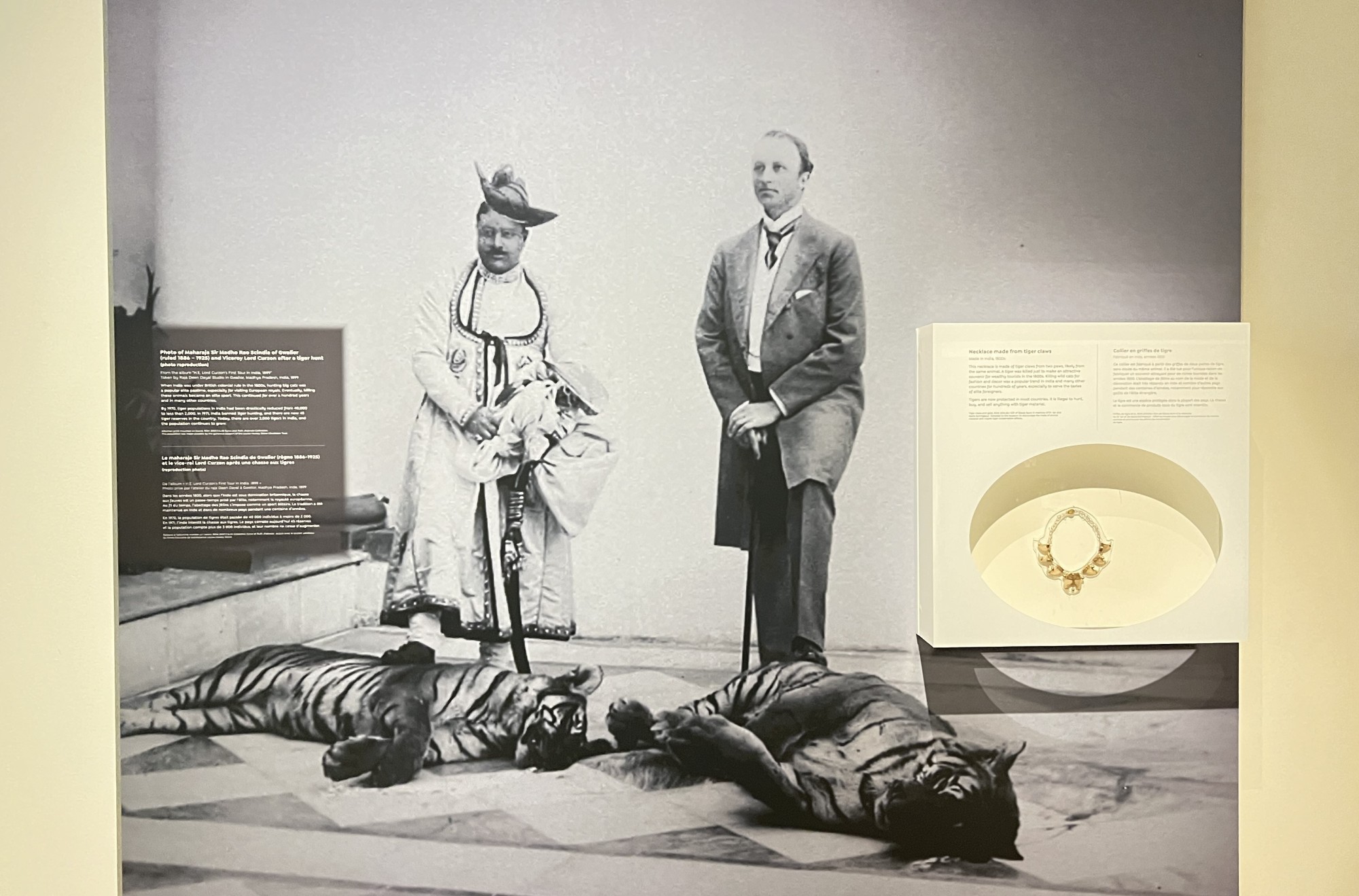

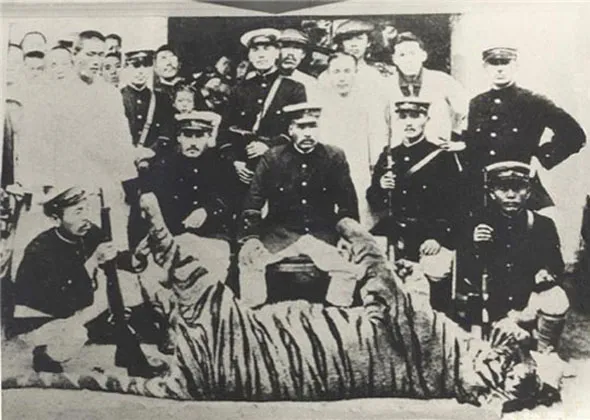

특히 19세기 박제술과 트로피 문화는 제국주의 식민의 관행에 뿌리를 두고 있다. 인도와 영국의 식민지 관계, 한국과 일본의 식민지의 관계는 동물들의 트로피 헌팅 사진들을 통해 잘 드러난다. 인간의 자연과 동물에 대한 지배 욕구의 문법은 식민의 통치와 지배의 문법과 연결되었다. 사냥 동물은 (그 당시로는) 이상화된 몸의 형상으로 박제라는 사물이 되고 전리품이 되어 인간과 권력의 질서에 편입되었다. 그 행위는 동물 신체의 박제만이 아니라 착취적 식민의 역사를 박제하는 것이기도 했다.

트로피 헌팅 혹은 망가진 트로피

이러한 질문은 컴퓨터 과학의 층위에서 어떠한 집단적 기록(혹은 데이터셋)을 통해 드러날 수 있는지에 대한 리서치로 이어졌다. 동물의 초상과 박제를 인공지능의 잠재 공간을 통해 드러내어 보는, 일종의 ‘합성 민속지학(synthetic ethnography)’2의 접근을 시도해 보기 위한 것이기도 했다. 이는 현실에서 추출한 ‘렌즈 기반 이미지 (lens base image)’뿐 아니라 ‘생성 이미지(computation base image)’를 함께 다루는 방법이기도 했다.

먼저 생성인공지능을 통해 인간과 (야생) 동물 간 관계를 살펴 보기 위해 ‘트로피 헌팅’이라는 문화가 생성 모델에서 어떻게 재현되는지를 실험했다. 이는 트로피 헌팅에서 드러나는 동물의 초상, 그리고 재현되는 문화적 관습과 형태 등의 시각적 문법이 어떻게 생성 모델에서 반영되고 있는가에 대한 질문이기도 하다.

2

Gabriele de Seta, et. al., “Synthetic ethnography: Field devices for the qualitative study of generative models”, SocArXiv, July 15, 2023. (https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/zvew4).

대부분의 이미지는 남성은 사파리 혹은 카무플라주 패턴의 복장을 하고 라이플을 들고 자부심 을 드러내는 표정과 자세로 서있다. 배경은 많은 경우 석양의 붉은 기운이 감도는 사바나이다. 이 낭만적 배경을 뒤로, 남성 옆에는 야생성이 사라진, 인간에 순종하는 자세의 큰 동물이 있다. 이미 죽은 동물이지만 살아 있는 것처럼 조작된 이런 자세는 구글 검색에서 찾을 수 있는 실제 트로피 헌팅 사진과 흡사하다. 즉 모든 시각적 문법들이 비슷하게 반영되어 있다.

흥미로운 것은 종종 동물들이 장엄한(majestic)한 느낌으로 강화되거나 신화화되어 생성되는 경우가 있었다. 또한 한편 주요한 패턴 중 하나로 라이플이 빠짐없이 등장하며, 종종 비율적으로 크게 도드라지게 드러나는 경우가 있었다. 이는 일견 너무나 당연하고 예측 가능한 것이었다. 하지만 흥미로운 것은 이 패턴(라이플)은 프롬프트의 조정을 통해서도 쉽게 삭제되지 않았고, 기묘한 흔적을 남겼다는 것이다.

사실 이러한 연관성의 가중치는 단지 라이플에만 해당하는 것이 아닐 것이다. 이를테면 결혼사진에서 드러나는 신부의 웨딩드레스, 소방관과 소방 호스, 경찰관과 경찰봉 등, 문화적 고정성을 반영하는 수많은 상관관계의 강한 가중치와 별다르지 않은 사실이기도 하다. 따라서 이것은 AI의 ‘편향성을 폭로’하거나 ‘윤리적 문제’를 이야기하는 것이기 보다, 이 가중치를 가지고 노는 의도적 놀이 혹은 AI에 집합적으로 반영된 인간의 문화에 대한 풍자적 ‘트로피 수집’과 비슷한 것일 수 있을 것이다.

우리는 라이플의 가중치에 반할 다양한 반대적 개념과 태도, 존재, 사물 등을 지속적으로 인풋(input)하며 라이플을 삭제하거나 바꾸려 시도를 해보았다. 이를테면 아기, 식물 심기, 기도하기, 자연관찰 망원경 등 그 가중치를 상쇄하거나 대치할 만하다고 여겨지는 수많은 프롬프트를 시도해 보았다. 이것은 우리가 예상했던 것보다 훨씬 데이터셋과 분류, 인간의 문화적 전형성을 줄타기 하며 기계학습의 혼란스러운 긴장을 유도하는, 결과를 예측하기 어려운 놀이이기도 했다.

다양한 시도에도 불구하고 이 학습된 강한 패턴은 대부분 라이플의 유령을 남겼다. 그리고 GPT는 끊임없이 ‘라이플이 생성되지 않았음’을 확신하였다. 이것은 흔히 일반적으로 학습의 미완성 과정에서 나오는 환각이라고 하기 어려운 부분이었다. 손상된 모델 혹은 매개변수 조정이 필요한 모델로 볼 수도 있지만, 우리는 그 패턴이 모델 깊숙이 각인되었다는 의미에서 ‘머슬 데이터(Muscle Data)’로 이름 붙였다.

프롬프트에 따라 라이플을 다른 형태와 용도로 바꾸려는 기계의 강박적 노력은 총이라는 형태와 사물의 위상을 변형하며, 총을 무력하게 드러낸다. 하지만 총이라는 것이 인간의 역사에 기입된 사물의 실존성은 여전히 사라지지 않는다는 점에서 이것은 근육 기억과 비슷했다.

우리는 어느 기계 모델에 정착해 유령처럼 사라지지 않고 인간의 욕망과 표현을 대리하는 사물로 재현을 반복하는 이 글리치들을 ‘망가진 트로피’, 혹은 ‘망가진 전리품’으로 전유했다. 마치 잘못 박제된 동물들(botched taxidermy)처럼 말이다. 어쩌면 이것은 인간의 권력과 폭력을 이끌어 온 기술에 대한 아이러니한 유머일 수도 있고, 혹은 라이플 자체를 망가진 기술과 같은 것으로 보는 것일지도 모르겠다.

AI가 생성한 이미지는 벌써 거의 흥미롭지 않다. 그러나 이러한 잠재 공간의 유희와 생성물을 통해 특정 루프에 갇힌 알고리즘이 그 강박을 드러낼 때, 우리는 그것을 통해 드러나는 인간의 역사를 흥미롭게 바라보게 된다.

인간 중심성과 관념을 유희하는 일종의 소극이 된 리서치는, 아직 명확하게 정의되지 않은 합성 민속지학의 개념을 더듬으며, ‘동물의 초상’을 둘러싼 인간 중심성에 대한 리서치로 이어질 예정이다.

Ideal Animal Image or Trash Data

The practice of capturing animals as visual images, observing them, and recording them reveals the relationship between humans and non-humans. This relationship shows how humans have used or misused the existence and image of animals over time, and what cultural intentions have been inscribed upon them. In particular, capturing the unpredictable movements of wild animals in photographs is challenging. The animal images searched on the internet or seen in typical nature documentary photographs rich with information can, in fact, be said to be images that are deeply ingrained with the visual grammar of how humans view wildlife.

In the case of trail cameras (unmanned cameras) that exclude human vision, the captured images of wild animals reveal a broader variety of aspects, because these cameras do not (or cannot) capture animals in ideal poses like human photographers do. Instead, they randomly capture unexpected angles or partial views of the animals. As a result, many of these photos are considered ‘unusable’ within the framework of human visual standards.

During Unmake Lab’s work process, when experimenting with such photos as a dataset for machine learning, there was a scene where an interesting discovery could be made. When images extracted from trail cameras—including those that were cropped, overly zoomed in, or captured random aspects of wild animals—were used as a dataset and processed through machine learning, the images of animals were predominantly generated as side or frontal views. This is likely because the animal data that existing artificial intelligence has been trained on primarily consists of idealized images within human visual perspectives, such as side or frontal views, and the pattern is learned through transfer learning and generated.

Alternatively, trail camera footage often generates data that could be considered ‘trash data’ due to its random poses and unexpected angles, which is why it may have been excluded during the preprocessing stage. Also, in the case of endangered species, it may be due to the limited amount of available data, caused by their physical rarity, that leads to underfitting in the machine learning process. Just like this, the data bias related to race and gender that exists within human culture can also appear in relation to non-human animals in a different way. This is particularly prominent when applied to real-world environments, where the broader and less predictable context of nature often leads to more mismatches.

This process of work and research raised the question of what an ‘animal portrait’ is, and this text is a record of that research, with an emphasis on ‘taxidermy.’ Of course, this is not only about the existing cultural context but also addresses issues such as classification problems and training datasets together, both of which are being repeated in the field of computer science.

Moon Bear’s Crescent Mark or Botched Taxidermy

Contemporary taxidermy, which represents animal portraits, is rooted in the history of animal preservation. However, as seen in the example above, taxidermy takes on different cultural meanings depending on who wants to preserve the animal and why. The custom of taxidermy has been linked to the aspirations of natural scientific research and colonial practices,1 and today it is associated with issues of wildlife conservation and restoration. Yet, at the same time, it still ties into the culture of trophies. Most taxidermied animals, after death, are represented as though they are alive due to their body and facial expressions, capturing the specific characteristics and expressions of their species in a particular condition. Taxidermy is about preserving the animal’s body, but more accurately, the materiality of taxidermy is preserving the skin.

The skin of taxidermied animals embodies socio-cultural meanings that allow us to contemplate the current relationship between humans and non-humans, while also reflecting humanity’s governance over nature and animals. In other words, ‘taxidermy’ exists as an interface between humans and non-humans. We too collected various taxidermied animals for datasets during our process, and a significant number of distorted specimens were found. These botched taxidermies, occupying space in natural history museums or relegated to their storage, made us wonder about the human gaze and intent embedded within them as well.

1

Joanna Page, Professor of Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge and Director of CRASSH (Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities), states that taxidermy was central to the imperialist, capitalist, and white cultural preservation efforts of museums. “Their more critical or creative approaches have been described as “botched taxidermy,” “rogue taxidermy” or “speculative taxidermy.””, Joanna Page, Decolonial Ecologies, The Reinvention of Natural History in Latin American Art, Open Book Publishers, May 3, 2023, p. 201 ( https://books.openbookpublishers.com/10.11647/obp.0339/ch6.xhtml)

Particularly, taxidermy and the culture of trophies in the 19th century are deeply rooted in the practices of imperialist colonization. The colonial relationships between India and Britain, as well as Korea and Japan, are well illustrated through trophy hunting photographs of animals. The grammar of human dominance over nature and animals was tied to the logic of colonial governance and rule. The hunted animal (of that time), often idealized in form, was transformed into an object through taxidermy, becoming a trophy and thus integrated into the order of human and power. This practice was not only preserving the animal’s body but also taxidermying the exploitative history of colonization.

Trophy Hunting or Botched Trophies

The question led to research on how such issues might be revealed through collective records (or datasets) in the realm of computer science. It was also attempting an approach to represent animal portraits and taxidermy through the latent space of artificial intelligence, adopting a method akin to ‘synthetic ethnography.’2 This approach not only dealt with ‘lens-based images’ extracted from reality but also brought ‘computation-based images’ together.

To begin, we experimented with how the culture of ‘trophy hunting’ is represented within generative models, as a way to explore the relationship between humans and (wild) animals. This is also a question of how the visual grammar, including animal portraits and cultural practices and forms represented in trophy hunting, is reflected in generative AI models.

2

Gabriele de Seta, et. al., “Synthetic ethnography: Field devices for the qualitative study of generative models”, SocArXiv, July 15, 2023. (https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/zvew4).

Most of the generated images depict a man dressed in an outfit with safari or camouflage patterns, holding a rifle, standing with a proud expression and stance. The background often features a savannah, bathed in the reddish glow of a setting sun. With this romanticized backdrop, the man stands next to a large animal that is posed to appear submissive to humans, having lost its wildness. This posture, which is manipulated as if it is alive despite being dead, closely resembles real trophy hunting photos that can be found through a Google search. In other words, all the visual grammar is similarly reflected.

What is particularly interesting is that, in some cases, the animals were generated in a way that often amplified their majestic qualities or mythologized them. Another consistent pattern in these images was the prominent presence of a rifle, which was often exaggerated in scale, making it stand out. This was both predictable and unsurprising. However, one intriguing aspect was that even when the prompt was adjusted, this pattern (of the rifle) was not easily removed and left strange, lingering awkward traces behind.

In fact, this weighted correlation might not be limited to the rifle alone. It is not much different from many other strong correlations reflecting culturally fixed associations, such as a bride’s wedding dress in wedding photos, a firefighter with their hose, or a police officer with their baton. Therefore, rather than simply ‘revealing AI’s bias’ or discussing ‘ethical issues,’ this can be seen as an intentional play with these weights, or a satirical ‘trophy collection’ of human culture collectively reflected in AI.

We continuously attempted to remove or replace the rifle by inputting various opposing concepts, attitudes, beings, and objects to counterbalance its weighted significance. For example, we tried numerous prompts such as a baby, planting, praying, or a nature observation telescope—ideas that we believed could offset or substitute the weight. This turned out to be a far more unpredictable play than we anticipated, navigating the fine line between datasets, classification, and the cultural archetypes ingrained in human behavior, inducing chaotic tension within machine learning.

Despite various attempts, this deeply ingrained pattern often left behind the ghost of the rifle, and GPT repeatedly asserted that ‘no rifle was generated.’ This phenomenon could not easily be dismissed as a typical hallucination arising from an incomplete learning process. While it might be assumed to be a damaged model or one requiring parameter adjustments, we coined it ‘muscle data,’ implying that the pattern is deeply imprinted within the model.

The machine’s obsessive effort to alter the form and function of the rifle according to the prompt transforms the shape and status of the object—the gun—rendering it powerless in its new context. Yet, this was similar to muscle memory in that the existential reality of the gun, etched in human history, still does not disappear.

We appropriated these glitches, which cling to certain machine models, refusing to vanish like ghosts and endlessly reproducing as objects that stand in for human desire and expression, as ‘botched trophies’ or ‘botched spoils’—much like botched taxidermies. Perhaps this is an ironic humor directed at the technologies that have long served human power and violence, or perhaps it reflects a view of the rifle itself as a broken technology.

The images generated by AI are already almost uninteresting. However, when the algorithm, trapped in a particular loop through the play and product of latent space, reveals its obsessions, we find ourselves intrigued by the human history it exposes.

The research, which became a kind of play on anthropocentrism and its ideas, will explore the yet-undefined concept of synthetic ethnography, followed by research on anthropocentrism with a focus on ‘animal portraits.’