순환적 구조 만들기

Making Circular Assemblages

한적한 습지의 가장자리에 서서 발밑의 세계에 귀를 기울인다. 땅과 물이 만나 섞여 세상의 기원을 연상시키는 습지에는 수많은 생물들이 얽혀 살아간다. 그곳의 흙 속 가장 작은 미생물의 세계에는 전자적 생태계가 있다. 이 연구는 그 비밀스러운 공간에서 시작된다. 자연 속에서 분해될 수 있는 대안적 전자 시스템을 고민하고, 그 과정을 예술 작품에 접목시키고자 하는 모험담이다.

미디어아트에 필수적으로 쓰이는 툴인 컴퓨터, 좀 더 넓게 전자기기의 기원을 파헤치다 보면, 전자 부품들의 생산 과정이 얼마나 지구 환경에 파괴적인 영향력을 행사하는지 알 수 있다. 인간이 만들어 내는 다양한 합성 물질과 땅 깊은 곳에서 퍼 올려 가공하고 멀리 배송하는 물질의 산업적 흐름은 지구의 물질대사를 교란시킨다. 한 번쯤은 이에 대한 프로젝트를 통해, 전기회로를 이루는 물질들을 탐구하고 ‘전기’, ‘컴퓨터’, 그리고 ‘컴퓨테이션(computation)’이란 어떤 것인지에 대해 좀 더 깊게 사유해 보는 시간을 가지고 싶었다.

이번 연구는 대안적인 재료로 전기발전 시스템을 만들어 보는 시도가 중심이 되어 이루어진다. 전기발전기의 대부분 혹은 전부를 자연 분해될 수 있는 재료로 구성되게끔1 재료 실험, 디자인 연구, 그리고 기능적 실험을 진행한다. 이 발전기는 미생물 연료전지(Microbial Fuel Cell)라는 기술을 사용한다. 흙 속에 살아가는 박테리아의 전기화학적 작용으로 전기를 생산하는 구조물이다. 이 작은 미생물은 오래된 숲의 연료, 퇴적된 유기물을 먹고 몸속에서 분해하여 물질의 원자 단위 변형을 일으킨다. 분해된 유기물은 가스, 양성자, 그리고 전자가 되어 미생물의 몸 밖으로 나온다. 이렇게 뿜어져 나오는 전자가 흘러 전기가 생성된다. 미생물 연료전지는 생물 고유의 순환 작용을 통해 전력을 얻는다.

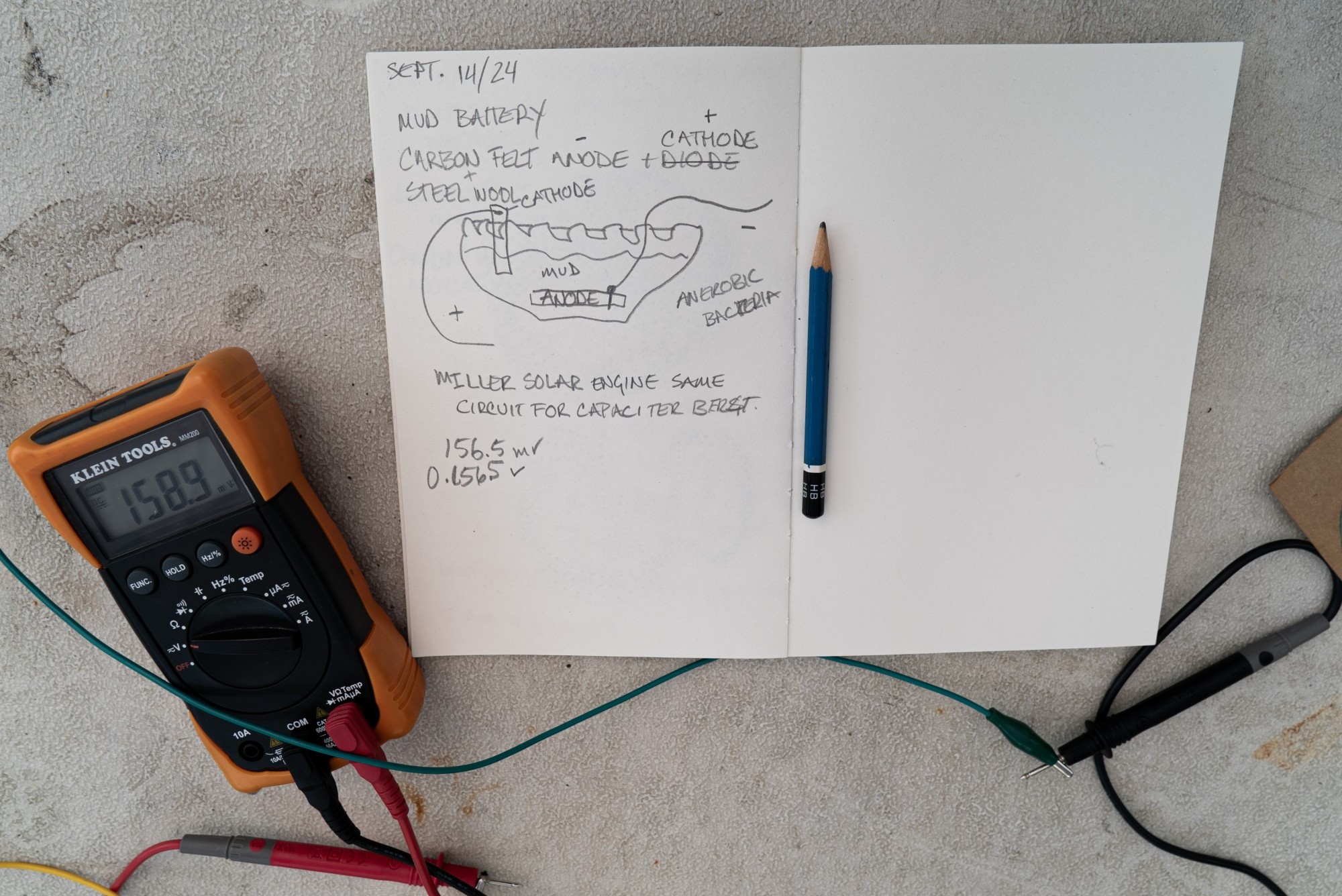

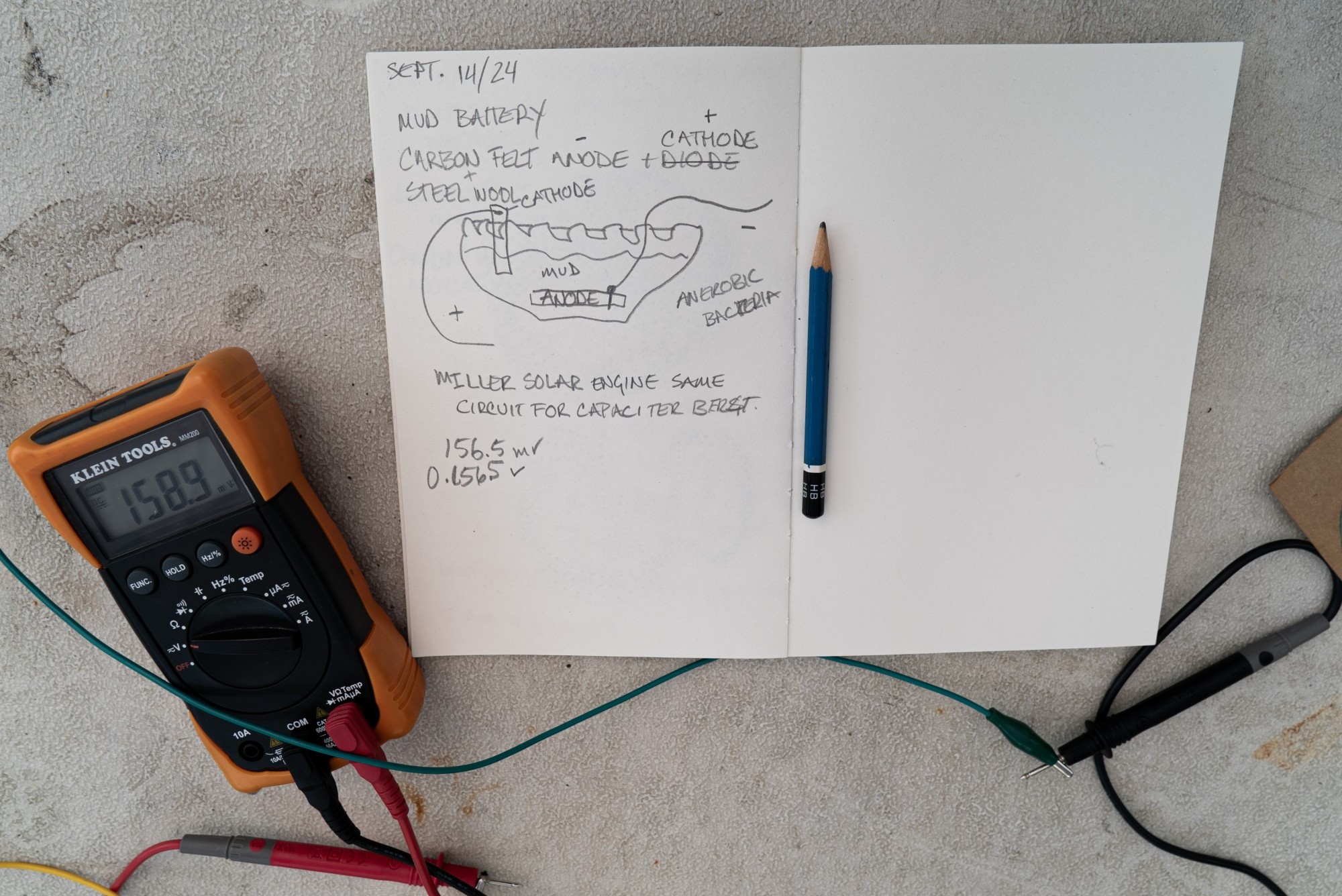

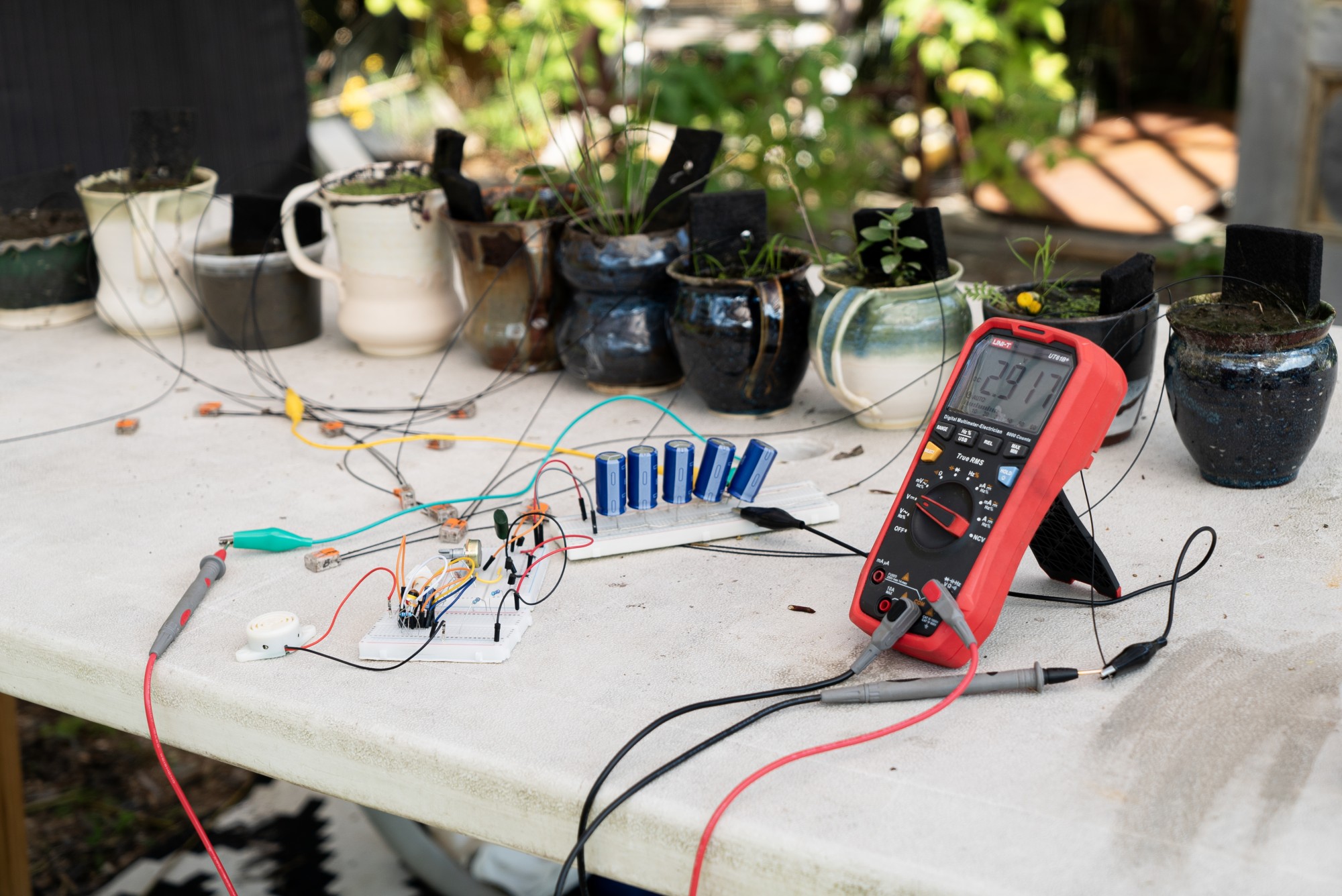

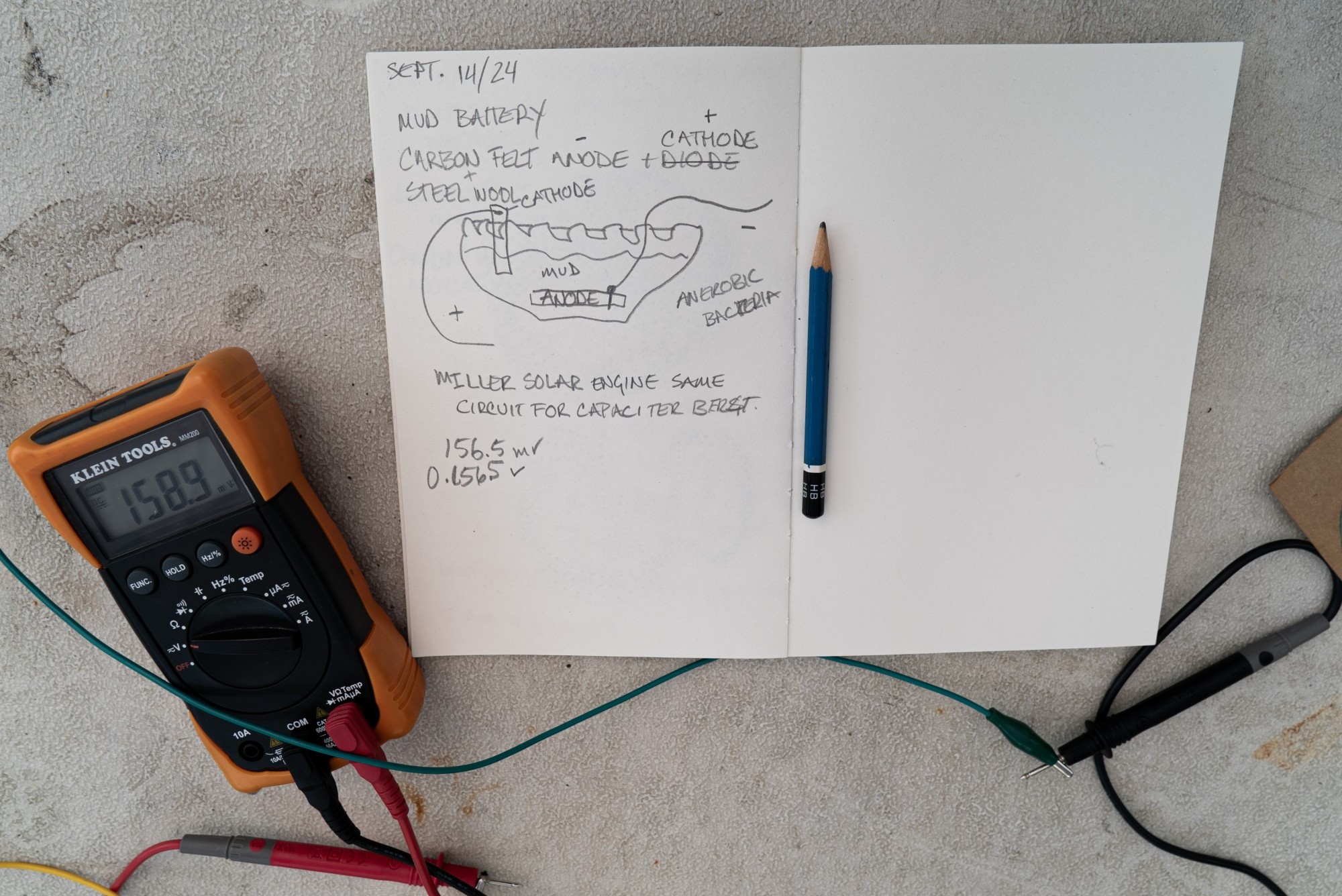

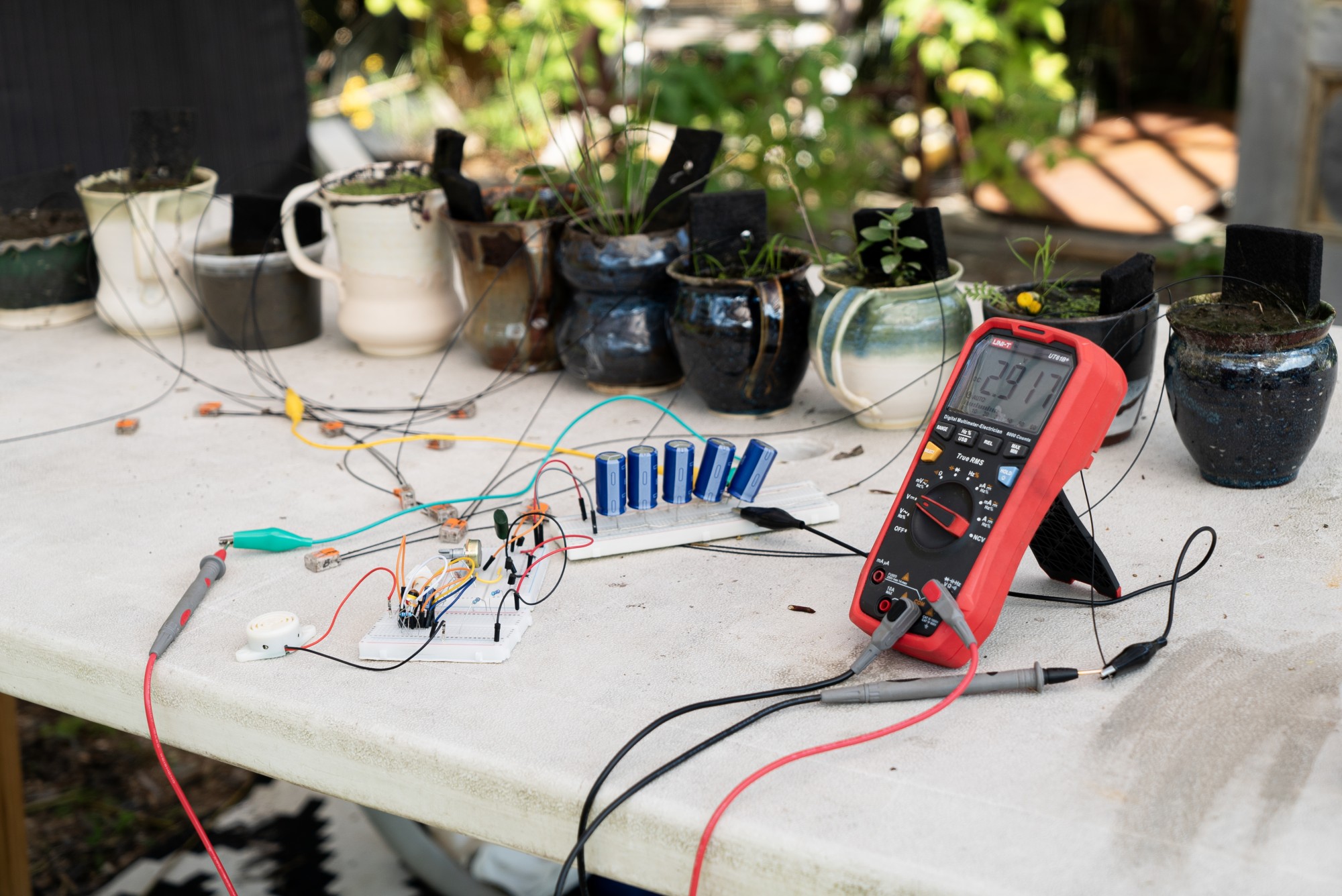

연못과 강의 깊은 바닥, 어둑한 흙 속에는 혐기성 박테리아들이 조용히 전자를 생성하며 살아가고 있다. 전기 생성 박테리아는 물에 잠겨 있는 흙 속이라면 어디서든 발견할 수 있다. 작은 컵 속에 연못의 흙을 퍼서 담고, 전극을 흙 밑과 흙 위에 하나씩 설치하면 미생물 연료전지를 만들 수 있다. 전극은 탄소 펠트나 스테인리스스틸 스펀지를 사용한다. 전극은 녹슬지 않으면서 전기가 통하는 물질이되, 스펀지와 같이 표면적이 큰 재료를 사용한다. 전기 생성 박테리아는 흙 속에 묻혀 있는 전도체에 붙어 살아가기를 좋아한다. 유기물을 분해하여 만들어 낸 몸속의 전자를 전도체를 통해 외부로 전달하고자 하기 때문이다. 박테리아들은 전극에 붙어 스스로를 복제한다. 흙을 퍼 전지를 만든 직후 전압은 0V이거나 더 낮게 잡힌다. 시간이 지나면서 박테리아 숫자가 기하급수적으로 늘어나 전극의 표면에 생물막(biofilm)을 형성하며 전기 생산량도 증가한다. 약 일주일 정도가 지나면 개방회로 기준 약 0.5V~0.7V 정도의 전압이 잡히고, 전류는 약 2.5mA 정도가 나온다.

1

“자연 분해 가능한 컴퓨터”라는 주제는 내가 2024년 6월 크리에이티브 코딩 위트레흐트(Creative Coding Utrecht)에서 참여했던 전시 《Composting Computers》에서 영감을 얻은 것이다.

이렇게 얻어지는 전력은 참으로 소박하다. 이런 한계가 때로는 창의력의 원동력이 되기도 한다. 나는 도시의 아파트에서 살며 230볼트의 전기를 물 쓰듯 쓰는 데에 너무 익숙하고, 그렇기에 도시인들에게 전기라는 것은 콘센트에 플러그를 꽂으면 원하는 만큼 나오는 부족함이 없는 에너지에 가깝다. 만일 어떤 전자기기가 박테리아가 생산하는 전기에 의해 작동한다면, 우리가 기존에 가지고 있는 기기의 작동 방식을 버리고 훨씬 더 천천히 자연의 리듬에 맞추어 기능하는 기기를 받아들여야만 한다. 박테리아는 인간이 원하는 만큼 원하는 때에 전기를 생산하지 않는다. 오늘의 날씨, 온도, 습도, 토양의 영양분과 공생하는 식물들의 상태 등이 박테리아의 대사 활동에 영향을 미치기에, 전기의 생산도 그에 영향을 받아 동요한다.

철학적이면서도 예술적인 관점에서 볼 때, 이 프로젝트는 시간성(temporality), 전도성(conductivity), 물 관리(water management), 이동성(mobility), 그리고 돌봄(care)과 같은 개념들과 깊이 맞닿아 있다.

특히 시간성은 이 연구의 주요한 화두이다. 무한히 이어지는 ‘딥 타임(deep time)’2이라는 개념 속에서 재료와 사물을 바라보는 태도를 제안하고자 한다. 예를 들어 유시 파리카(Jussi Parikka)가 『미디어 지질학(Geology of Media)』에서 다뤘듯이, 오늘날 우리가 쓰는 컴퓨터는 수백만 년 전부터 지구의 지층 속에 자리해 온 광물로부터 비롯된다. 이 광물들은 아주 짧은 순간, 길어야 몇 년 동안 인간의 손에서 컴퓨터라는 형태로 사용되다가, 버려진 후 다시 수백만 년이라는 긴 시간 동안 전자 폐기물로 존재하게 된다. 이렇게 시간의 거대한 흐름 속에서 ‘컴퓨터’라는 모습으로 머무는 순간은 그저 찰나에 불과하다.3

이러한 관점으로 재료를 살펴볼 때, 그 재료가 인공물로 존재하기 전과 후의 생애를 고려하는 일은 의미를 가진다. 예술 작품, 제품 혹은 어떤 무언가를 만들 때 내가 사용하는 재료가 어디에서 왔으며, 앞으로 어떤 길을 걷게 될지를 상상해 보는 것이다. 이는 결국 퇴비화(compostability)라는 개념과 맞닿는다. 재료가 인간의 짧은 사용 기간을 넘어, 그 이후에도 의미 있는 존재 방식을 가질 수 있다면 어떨까. 이 질문은 깊은 시간에 대한 존중에서 비롯된다. 만약 어떤 물건을 단 20년 쓰고 버릴 예정이라면, 굳이 썩지 않고 남아돌아 환경을 해치는 플라스틱 대신 나무를 사용할 수도 있다. 현대 기술이 목표로 삼은 ‘오류 없는’ 작동 덕분에 우리는 완벽하게 작동하는 물건을 얻었지만, 동시에 그것들은 결코 분해되지 않고 오랜 시간 잔존하는 ‘오류 많은’ 폐기물이 되어 버렸다.

물건이 부패하고 사라질 수 있다는 사실을 부정적으로만 볼 필요는 없다. 인간의 시선에서 ‘망가질 수 있음’으로 보이는 이 특징은 멀티스피시즈(multispecies) 맥락에서는 더 많은 생물들이 그 물질을 이용할 수 있게 하는 ‘생물학적 가용성’을 의미하기도 한다. 나는 인간 기술이 앞으로 생물학적 순환 속에 더 자연스럽게 들어맞는, 제어 가능하면서도 생물에게 더 쉽게 흡수될 수 있는, 결국은 썩고 사라져 자연으로 돌아가는 시스템으로 진화해야 한다고 믿는다.

시간성을 에너지 생산의 속도와 관련하여 생각해 본다. 박테리아들이 만들어 내는 전력은 아주 적은 양이지만, 이는 자연 생태계가 지닌, 인간의 시스템보다 느린 박자와 함께한다. 이 작은 세균들은 온도 변화에 민감하게 반응하고, 계절과 일교차에 따라 전기 생산량 또한 출렁인다. 이처럼 박테리아가 주도하는 전자 시스템은 현대 기술이 요구하는 즉각적이고 빠른 반응 속도와는 결을 달리한다. 이 느리고 불균등한 흐름은 다른 가능성을 보여준다. 박테리아와 식물, 계절과 환경이 서로 얽혀 만들어 내는 이 에너지의 리듬은 인간으로 하여금 기대와 규범을 재조정하도록 요구한다. 더딘 흐름, 드문 공급, 간헐적인 작동—이 모든 것은 인간이 우리와는 다른 존재의 박자에 맞추어 걸음을 늦추고, 기다리고, 수용하는 법을 터득하도록 돕는다.

컴퓨터는 물질과학이 빚어낸 결과물이다. 축축한 흙을 재료로 작은 발전소를 만들어 보는 과정에서, 나는 전자 회로라는 것이 얼마나 정교하게 구성된, 전기를 철저한 제어 하에 움직이게 하는 길인지를 깨닫게 되었다. 그 길 위에서 전기를 잘 흐르게 하는가 혹은 막아서는가를 판단하는 각 요소는 저마다 타고난 물질적 속성을 가진다. 제각각 다른 특성을 지닌 광물, 금속, 그리고 합성 물질들이 모여 하나의 전자 회로를 이루고, 오류 없이 정확한 속도로 전자의 흐름을 제어할 때, 우리는 ‘컴퓨터’라 부를 만한 기계를 손에 넣는다.

하지만 예술가로서 나는 문득 궁금해진다. 꼭 공장에서 가공한 고정밀 전자 부품이 아니더라도, 우리 주변 어디서나 발견할 수 있는 재료—물과 같은 액체, 공기 중에 떠다니는 먼지와 가스, 땅 위의 돌 등—가 비슷한 전기적 특성을 지닌다는 것을 인지하면 어떨까? 이렇게 손쉽게 구할 수 있는 재료들을 다양하게 모아 특정 순서로 배열하고 전기의 흐름을 조정한다면, 조금 다른 컴퓨터를 만들 수 있는 것일까? 이런 상상을 할 때면, 마치 넓은 자연의 들판과 숲, 물웅덩이, 계곡이 거대한 회로가 되어 서로 신호를 주고받는 네트워크처럼 느껴진다.

2

Jussi Parikka, Geology of Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015)

3

이 관점은 2024년 크리에이티브 코딩 위트레흐트에서 주프(Zoöp) 워크숍 도중 예술가 테운 카렐세(Theun Karelse)가 언급한 것이다.

물을 예로 들어보자. 모두에게 익숙한 이 물질은 광물을 녹여 내고 전기가 흐를 수 있는 통로를 만든다. 물론 순수한 물은 전기를 전도하지 않지만, 세상에 존재하는 대부분의 불순물이 용해된 물은 전도성을 갖춘다. 이 전도성의 폭은 매우 넓어서, 바닷물은 1,000에서 7,000mS/m나 되는 높은 전도도를 지니는 반면, 민물은 보통 10에서 700mS/m 정도, 그리고 영구 동토층은 0.01에서 3mS/m 사이4에 불과할 정도로 현저히 낮다. 또한 주변을 둘러보면 나무나 밀랍 같은 절연체들이 있다. 이렇게 주변의 수많은 물질들의 전기적 특성에 주목하는 순간, 나는 전자 기기를 좀 더 넓은 범위에서 상상하는 새로운 가능성을 본다. 물론 이런 식으로 컴퓨터와 비슷한 무언가를 만들 수 있는지 의문이고(예를 들어 반도체의 성질을 가진 재료는 그저 동네 땅 위의 돌들 사이에서 찾기는 힘들다), 만일 가능하더라도 이러한 시스템은 완벽과는 거리가 멀다. 오류나 고장에 취약하고 덩치가 크며, 외부 기후나 환경 조건에 민감하게 반응한다. 이는 자본주의적 효율이나 정확한 시간 엄수와는 정면으로 어긋난다.

미디어 아티스트로서, 나는 관객들로부터 항상 완벽하게 작동하는 미디어 작품을 기대받곤 한다. 예술가는 때때로 자신의 거주지와는 멀리 떨어진 해외 레지던시나 전시 공간으로 초대받는다. 균과 흙을 다루는 내 프로젝트가 이런 기대에 부응하는 일은 쉽지 않다. 박테리아가 만들어 내는 전력은 극히 미미할뿐더러, 국경을 넘어 흙과 박테리아를 옮기는 일은 금지되거나 까다로운 검역을 거쳐야 한다. 외래 생물이 그곳의 생태계를 오염시키거나 침투종이 될 수 있다는 우려 때문이다.

끊임없이 변하고 흐르는 생명을 가진 재료를 다루는 일이 때로는 나를 지치게 한다. 반면 미술관은 멈춰진 시간 속 온도와 습도 조절이 가능한 화이트큐브(white cube)로 존재하며, 무균 상태의 예술 작품들로 채워져 있다. 반면 이 작품은 이동성과 통제의 문제와 씨름한다. 작품을 옮기기 위해서 디지털 장비 대신 흙과 박테리아를 옮겨야 한다. 여기서 떠오르는 의문이 있다. 정말로 예술 작품이 그렇게 멀리까지 이동할 필요가 있을까? 시간을 머금은 흙, 끊임없이 변화하는 생명체, 그리고 이를 둘러싼 규제와 환경—이 모든 것이 예술의 이동성과 존재 방식을 다시금 생각하게 만든다.

마지막으로 다루고 싶은 주제는 바로 ‘돌봄’이다. 이 작업에서 에너지는 소비하는 대상이라기보다는 보살피고 길러 내야 할 무엇으로 자리한다. 나는 전기 소비자의 수동적인 역할에서 한발 물러나, 에너지를 함께 생산하고 유지하는 능동적인 협력자로 함께한다. 이 지점에서 나는 단순한 창작자에서 일종의 퍼포머(perfomer)가 된다. 흙과 박테리아, 물과 전극, 전선을 모으고 이어 붙이며, 이들의 유기적 흐름을 이어가기 위해 애쓴다. 그런 과정 속에서 내가 이 프로젝트에 쏟는 노동에 대해 생각하게 된다.

4

전도도 측정값은 M. N. Nabighian 편집의 Electromagnetic Methods in Applied Geophysics (1988) 중 G. J. Palacky의 “Resistivity Characteristics of Geologic Targets” 장(55쪽, 그림 2)에 실린 그래프에서 참조한 것이다.

어떤 종류와 형태의 작품을 만들 것인지, 혹은 어떤 것을 의도적으로 만들지 않을 것인지에 대한 나의 선택은 작업하는 방식과 노동의 성격을 규정한다.5 이 시스템의 기초를 세우고 동시에 돌보는 이로서, 나는 내가 구축한 생태계의 일부가 되어 간다. 스스로에게 묻는다. “이 체계 안에서 나는 어떤 요소가 되고 싶은가?” 그 답변은 작품의 형태와 그 결실을 결정한다.

5

이 프로젝트에서 내가 예술가로서 어떤 역할을 수행하는지에 대해 동료 예술가 젬레 에라슬란(Cemre Eraslan)과 나눈 대화에서 영감을 받았다.

이 과정에서 놓치지 말아야 할 한 가지가 있다. 바로 이 실험들이 곳곳에서 한계에 부딪힌다는 점이다. 예를 들어, 내가 사용하는 탄소 펠트 혹은 스테인리스스틸 전극은 멀리 떨어진 어떤 공장에서 제작되어 배달된다. 그 공정에서 어떤 환경 오염이 발생하는지, 그 부품을 만들기 위해 일하는 사람들이 어떤 노동 조건에 놓여 있는지 나는 알기 힘들다. 이러한 단절된 상황은 나로 하여금 대안적인 재료를 찾아보게 만든다. 어떤 경우는 대체 재료를 찾기도 하지만, 전극과 같이 대체재를 찾기 어려운 요소들이 있다. 시스템을 이루는 각 재료를 깊이 들여다볼수록 이를 대체할 다른 재료를 구하는 일은 점점 더 막막해진다. 추출 기반(extractive)의 산업 구조에 조금도 의지하지 않고서 전기 발전기를 만드는 것은 물론, 그보다 더 복잡한 컴퓨터를 만드는 일은 사실상 불가능에 가까워 보인다. 심지어 이 미약한 실험에도, 나는 어쩔 수 없이 먼 곳의 산업 시스템에 의존하고 있다.

그럼에도 불구하고, 이 실천은 컴퓨팅과 그 물질적 생태계의 숨겨진 층위들을 더 넓은 시야로 바라볼 수 있는 계기를 마련해 준다. 컴퓨터라는 존재가 어디서부터 시작되어 어떻게 물질과 전력을 끌어다 쓰고, 축적하고, 변화시키는지 관찰하는 일은 계산이라는 행위의 본질을 생각하는 데에 유용한 틀을 제공한다.

내가 ‘컴퓨터 생태학’이라고 부르는 개념은 컴퓨터가 생겨나고 소멸하기까지의 전 과정을 포괄한다. 자원이 어디서 발견되고, 채굴되고, 운반되며, 엔지니어링과 제조를 거쳐 우리 손에 쥐어지고, 사용된 뒤 결국 폐기되는 전 과정과 그 모든 단계마다 연결되어 있는 수많은 다른 생물들, 사회들, 장소들의 관계망을 하나의 유기적 흐름으로 바라보는 일이다. 나는 이 선형적이고 추출적인 프로세스를, 적어도 일부만이라도, 자연 생태계와 닮은 더 순환적인 시스템으로 바꾸는 실험을 해 보는 것이다.

수많은 요소들이 어우러지는 혼합적 구조물 속에서 전기는 단순한 에너지원이 아니라 다양한 경로를 거치는 생명력의 흐름이 된다. 이러한 시도 속에서 나는 전기적 시스템이 품은 복잡성을 탐구하고, 동시에 시적이고 은유적인 형태로 그 복잡성을 표현하는 하이브리드 시스템을 만들어 보고 싶다.

This research explores alternative electronic systems that are compostable.1 It also investigates how these processes and their outcomes can become forms of art. Specifically, the research experiments with building a power plant that generates electricity through bacterial electrochemical processes, using mostly or entirely compostable materials. The aim is to replace elements in conventional electronics—often misaligned with nature’s metabolic cycles—with more circular systems and materials.

At the core of this exploration is microbial fuel cell (MFC) technology, which offers a way to capture the electricity produced by bacteria. The plant-based microbial fuel cell utilises anaerobic electrogenic bacteria naturally found in wetland soil. These bacteria thrive in containers fitted with conductive electrodes, made from carbon felt or stainless steel sponges. The plants, living in symbiosis with the bacteria, provide them with nutrients. Bacterial metabolism breaks down organic compounds in the soil, releasing gas, protons, and electrons as by-products. Although the amount of electricity generated is quite small (typically 0.5V and 2mA in an open circuit), creativity and engineering can find ways to utilise this low-voltage energy meaningfully and functionally.

1

This theme of “compostable computer” was inspired by the exhibition Composting Computers, which I participated in during June 2024 at Creative Coding Utrecht.

The circularity of the main catalysts for electricity generation—soil, bacteria, and plants—is central to this project. The challenge lies in understanding the ecological systems that drive electrogenesis in wet soil. Equally important are the material experiments aimed at building energy-harvesting infrastructures, such as waterproof containers, electrical wiring, and electrodes. This requires a careful examination of the global supply chain of both natural and synthetic materials. Each component in the experiments is evaluated in terms of how it is produced, used, and discarded, to develop a holistic understanding of the system being enabled—and the one being replaced. Additionally, I have experimented with electronic systems designed to operate on the low voltage and low current provided by bacterial electricity.

From a more philosophical and artistic standpoint, this project engages deeply with the concepts of temporality, conductivity, water management, mobility, and care.

Temporality has been a key subject in this research. Recognizing the “deep time”2 of materials and objects is crucial. As discussed in Geology of Media, computers are derived from minerals that have been part of Earth’s history for millions of years. For a brief moment—just a few years at most—these minerals are shaped into and used as a computer, and once discarded, they become e-waste for another millions of years.3 When we look at materials from this perspective, the time they spend as a “computer” is a blink in their vast geological existence. Acknowledging both the pre- and post-artifact lives of these materials raises an important question: How do we treat materials in our artwork, given this deep time? This question links directly to the idea of compostability. There is a beauty in creating works that consider the afterlife of the materials used. In order to respect deep time rather than short-term utility, I ask: if an object will only be used for 20 years, why use plastic instead of wood? Elimination of error in the object’s functioning has made well-functioning objects but malfunctioning waste. When an object is perishable, it may be seen as prone to failure from a human perspective, but in a multispecies context, it offers greater bioavailability. I believe that human technology should evolve to create more controlled bioavailable and perishable systems.

Temporality also plays a role in the pace of energy production. Bacteria produce only a small amount of energy, which aligns with natural ecosystems’ slower rhythms. They are sensitive to temperature, and the entire ecosystem fluctuates in response to both seasonal and daily weather changes. Electronic systems powered by bacteria must adapt to this pace. The urgency and speed that modern technology often demands are challenged by these natural systems, reminding us that bacteria, plants, seasons, and the environment have their own pace. This multi-species collaboration requires humans to adjust their expectations and norms to align with nature’s slower, more intermittent processes.

Computers are products of material science. By learning how to construct a power plant using wet soil, I have gained an insight into how electronics are intricately designed pathways that precisely control the flow of electricity. Each element in these pathways—whether it conducts or resists electricity—has specific properties. As an artist, I wonder: could I find raw natural materials(no matter liquid, airy, or solid) around me that possess the same electrical characteristics? Could I sequence these materials correctly and, in theory, build a computer?

2

Jussi Parikka, Geology of Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015)

3

This observation was mentioned by artist Theun Karelse during a workshop for Zoöp at Creative Coding Utrecht in 2024.

Water, for example, is a familiar material that can dissolve minerals and become conductive. While pure water doesn’t conduct electricity, most impure water does. The conductivity of water varies significantly: seawater has a high conductivity, ranging from 1,000 to 7,000 mS/m, while freshwater typically conducts between 10 and 700 mS/m, and permafrost exhibits much lower conductivity of 0.01 to 3 mS/m.4 Natural insulators, such as wood and beeswax, also exist all around us, offering potential alternatives to synthetic materials. This consideration of natural materials in electronics opens up new possibilities. By selecting alternative materials with specific conductive or resistive properties, we can rethink how to rebuild electronic systems in experimental ways. This kind of system, even at its best, is prone to error or failure, the size is not very portable, depends highly on the external climate, and is closely tied to biological or ecological systems. However, it is a system that defies capitalist productivity or punctuality.

As a media artist, I often face expectations from cultural organisations, curators, and audiences to create media works that function flawlessly. Artists are sometimes invited to residencies and exhibitions abroad, far from their home base. However, for a project like mine, which involves working with bacteria and soil, meeting these expectations can be challenging. Beyond the fact that bacterial energy is minuscule, transporting bacteria and soil across borders is prohibited. They are classified as hazardous because they can contaminate ecosystems or become invasive in foreign environments. Working with living organisms that are always in flux can be tiring. Museums, in contrast, are filled with sterile artworks that show no signs of life, as if time stands still within the climate-controlled white cube. My work constantly grapples with issues of mobility and containment. It raises the question: Do artworks really need to travel so far?

4

These conductivity measurements were derived from a graph in Electromagnetic Methods in Applied Geophysics, edited by M. N. Nabighian (1988), Chapter “Resistivity Characteristics of Geologic Targets” by G. J. Palacky, p. 55, Figure 2.

The final topic I’d like to address is ‘care.’ In this work, energy is something to be cared for, nurtured, and cultivated. As the caretaker, I step away from the passive role of an electricity consumer and instead become an active, collaborative generator of energy. I embody the role of a performer, responsible for gathering, assembling, and sustaining the system. This shift makes me aware of my own labour within the project. The type of artwork I aim to create—or consciously refrain from creating—dictates my mode of working and the state of labour involved.5 As both an initiator and a caretaker, I become an integral part of the ecosystem this project establishes. I continually ask myself: What kind of element do I want to perform within this system? The answer to this question shapes the form and outcome of the resulting art piece.

5

This idea was inspired by a conversation I had with fellow artist Cemre Eraslan about my role as an artist within this project.

An important point to note in this process is that the experiments frequently face limitations. For example, the electrodes I use are manufactured in a distant factory, contributing to pollution in places far removed from my own environment. I am unaware of the labour conditions faced by those who produce these materials. This disconnection drives me to seek alternative materials, but finding substitutes that perform equally well is a significant challenge. The deeper I delve into the analysis of each material in the system, the harder it becomes to find replacements. It feels nearly impossible to construct an electricity-generating power plant, let alone a computer, without relying on the extractive systems already in place.

Nevertheless, this practice offers me broader insights into the hidden layers of computation and its material ecologies. Understanding the ecology of a computer—how power flows, is stored, and transitions—becomes a useful framework for analysing the nature of computation itself. When I refer to ‘computer ecology,’ I’m talking about the entire lifecycle of a computer: from locating resources, mining, transportation, engineering, and manufacturing, to consumption, utilisation, and eventual disposal of the electronics. By exploring how these linear, extractive processes can be (at least partially) transformed into more circular systems that collaborate with natural ecosystems, I wish to continue making hybrid systems that express the complexity of the electrical systems both in an investigative and poetic manner.